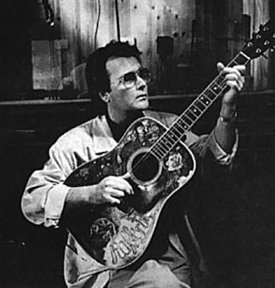

Folk Roots (1988)

Gerry Rafferty is one of the more elusive and enigmatic figures on this increasingly strange roundabout. A Scotsman bred on traditional music, he was never a proper folkie – not really – and his alliance with Billy Connolly in The Humblebums at the end of the ‘60s always seemed a bizarre blend of opposites, though Gerry maintains it was basically a happy relationship. His yearning for a more serious musical outlet came to fruition in several stormy years with Stealers Wheel, who produced some wonderfully persuasive music before splitting in disharmony and legal wrangles. The demise of Stealers Wheel left Rafferty exhausted and confused and while his former colleague Connolly soared to undreamed-of heights as an outrageous comedian, Rafferty retreated further and further into himself. But his return – when it came several years later – with the album City to City was spectacular. The single Baker Street became one of the best-selling singles of all time (as well as including one of the most famous sax breaks) and for a couple of years – flying directly in the face of the punk boom – Rafferty’s gentle melodies were considered the bee’s knees. And then Rafferty – always

an intensely private man whose skirmishes with the press

tended to be few and far between at the best of times

– disappeared. Now he’s back with an LP called North

and South – no less elusive than he ever was,

but a little more mellow about the particular twists and

turns that have dragged him around. CI: You’ve been away for a while. GR: About five years since the last album. I just decided to stop, though I hadn’t intended to stop for quite so long. I had quite a hectic period during the City to City time and I decided I wanted to do some travelling. So I did. CI: Where did you go? GR: Mainly Europe. And America. We spent nine months in Italy – and then I found myself wondering whether I should do another album. CI: Did you miss it when you were away? GR: No, not really. I can’t say that I did, but continued to write during that period. CI: Did you think you wouldn’t come back to recording at all? GR: What I wanted to do was to move into other areas … write film music, or music for the stage or something. I was bored rigid with myself, and I needed a new challenge. I did actually do some music for an American film that has failed to see the light of day and I did one or two bits of production. Hugh Murphy and I did an album for Richard and Linda Thompson which we actually financed but it never saw the light of day. CI: Why? GR: Oh, this was ’82 and I think they were having their own problems. It was a great album. It was the album that eventually became Shoot Out The Lights. What happened was they’d been dropped from Island and I’d been a big fan of Richard’s for a long time, so Hugh and I financed it. But we couldn’t get them a deal. It was unbelievable. There were no takers. And what happened was Joe Boyd came along and I think out of desperation because we’d been sitting on the album for six months, Richard and Linda decided to sign to Hannibal. Hey re-recorded most of the stuff that had already been done, and it became Shoot Out The Lights, but it wasn’t a patch on the album we had done. CI: Didn’t you think of forming your own label and putting it out yourselves? GR: We did, but I didn’t want to get that far into the business side of things. So the tape’s still sitting there on Hugh’s shelf to this day. CI: So are you nervous about coming back after so long? GR: No, it’s not about coming back – I don’t really feel I’ve been anywhere. CI: But you haven’t been in the public eye… GR: But even during the City to City and Night Owl period I was never in the public eye that much. I was always very conscious about keeping a low profile because that’s the way I like to go about it. And I don’t plan to be in the public eye too much now either. CI: But don’t you worry if people are still going to like your music. Tastes change… GR: Oh, I never worry about all that. When City to City came out and Baker Street and all that, I hadn’t done an album for over four years then because of the break-up of Stealers Wheel and all that. And you may recall that album came out at the height of the punk thing. Once you start worrying about fashion there’s no point in doing it. CI: So can you be objective about this album? GR: No, not really. It took a long time to make – over a period of a year and a half. And some of the songs I’ve lived with for three or four years. CI: Presumably the idea of North and South as title is a political thing? GR: Not especially, though it is, of course, a phrase that gets bandied about under the Thatcher term. There are a few references to it, but it’s more about the fact that I’m from the north – from Scotland – and I live in the south and the time I spend travelling between the west of Scotland and London. It’s more to do with that than the political thing. CI: Hmmmm…. GR: You don’t believe a word of that, do you, Colin? [Ribald laughter from the two participants] CI: Do you keep tabs on what’s going on in music? GR: No, I don’t take much note of what’s new or whatever. When I play music at home I tend to put on Irish traditional music, so I’m not really that aware of what’s coming up. CI: You’ve got Davy Spillane on the album, haven’t you? GR: Yes, I knew of him because of his work with Moving Hearts, so he was an obvious choice when I felt I needed some pipes. It worked out very well – he’s an excellent player. CI: Have you heard his solo album? GR: Oh yes, it’s excellent. It’s breaking new ground in lots of ways. CI: How did you come to write Shipyard Town? GR: Well that’s unashamedly nostalgic. My wife comes from Clydebank, which was the shipbuilding area. It was there where they built all the queens, Queen Mary and the QE2 and stuff like tat. I spent a lot of time over there when we first met and the song is just about that basically. An old-fashioned love song! CI: So tell me how you came to produce The Proclaimers! GR: Somebody from Chrysalis sent me a tape of Letter From America and asked if I’d be interested in producing it as a single. I was quite taken aback by the fact that it was just two voices and an acoustic guitar. The directness of it appealed to me, the immediacy of it, and the lyrics as well. So I said I’d love to get involved. And Hugh Murphy and I did it as a joint thing and it worked out really well. It was their first single and it did really well in the charts. They’re nice guys – they’ve got good heads on their shoulders. CI: Are you going to be doing any more stuff with them? GR: I don’t know. I would be up for it in the future if they wanted to. I think they’re really good. CI: I think they’re really bold, singing in such strident Scottish accents… GR: Yes, there’s a lot of people who’ve made a big thing of singing in the Scottish accents, which is good in one way, but you can take that stance too far. If half the people don’t understand what you’re singing about that defeats the purpose. I’m sure there were a lot of people in the south east who didn’t have a clue what the song was about – which is a shame because it’s a really good lyric. CI: Do you feel haunted by Baker Street? It’s what you’re always remembered for. GR: No, I don’t feel haunted by it. I suppose it’s become one of those songs like Whiter Shade of Pale or something that people always remember. I’m duly flattered. I’m pleased I was able to produce something like that, something so successful, because it was a good piece of work. CI: Even though they remember it for the sax solo as much as anything. Didn’t that become a bit of a millstone round your neck? GR: No, no, no. I don’t think that’s strictly true anyway. No doubt Baker Street opened me up to a much wider audience, but the City to City album sold over five million copies. It wasn’t just Baker Street that they were interested in. The only confusion at the time that I didn’t enjoy too much was the fact that a lot of people believed that the line was written by Raphael Ravenscroft, the sax player, but it was my line. I sang it to him. CI: Yes, wasn’t it originally conceived as a guitar line? GR: We tried various things. When I wrote the song I saw that bit as an instrumental part but I didn’t know what. We tried electric guitar but it sounded weak, and we tried other things and I think it was Hugh Murphy’s suggestion that we tried saxophone. We phoned Pete Zorn to do it, but he said his lip had gone and he couldn’t do it, but he gave us the names of five or six other people. We hadn’t heard of any of them, but one of the names was Raphael Ravenscroft so Hugh said with a name like that we’ll try him! So he turned up with this real beat up old saxophone; it was falling apart with the keys falling off and gaffer tape everywhere, but because Raph plays really, really hard it was just the right sound for the track. And the rest is history. CI: Did you find it a pressure afterwards to come up with something to match it? GR: No, there’s no point in even trying to match it. People think in those stereotype ways that because you’ve done something very successful you’re spending every waking moment wondering "My God, how do I do something as successful again?" But it’s never been in my nature to do that or try and follow it up. There’s no point. You’ve done that – what’s the point of trying to do it again? So I didn’t feel any pressure due to it – I was pleased the song drew attention to the album. I was much more pleased at the success of the album than the single. I think there were stronger songs on the album than Baker Street… though Baker Street had an interesting musical construction and it did have the sax line. CI: So when you write you don’t think in commercial terms? GR: Never? I’ve never written like that and wouldn’t know how to. It’s for the buying public to decide what they like. CI: Do you have any long-term career plans? GR: I’d like to do more production work. And I would like to think that at some point I could get involved with writing a musical – something that I’ve never done before. I’ve got various ideas in the back of my head… one thing I want to do is write something around the life of Robert Louis Stevenson, who’s a writer I much admire. I don’t know what form it would take, but something away from the format of ten or eleven songs on an album, which I’ve done. CI: You sound bored by the whole process… GR: There’s a thin line between being a songwriter and a singer and being personality. I’m not alone in that. Van Morrison is probably the prime example of somebody who quite deliberately places all the emphasis on the music he makes and refuses to take up the stance of being a celebrity. I understand it very well. If you feel uncomfortable with it you shouldn’t do it. It’s not for me – there are too many inherent contradictions. CI: Were you always interested in traditional music? GR: Oh yes. When I was a kid I knew stacks of traditional songs. My father was Irish so growing up in Paisley I was hearing all these songs when I was two or three. Songs like She Moves Through the Fair, which my mother sings beautifully. And a whole suite of Irish traditional songs and Scots traditional songs. But that was intermixed with lots of stuff, Thomas Moore and stuff like Mountains of Mourne, almost semi-music hall stuff that was written at the end of the last century, but which has its place. Thomas Moore was exceptionally gifted. So that was the environment in which I grew up. It was part of the natural tradition to sing. I have two older brothers and when we were very young we were singing three-part harmonies. And at parties, at Christmas and New Year you sung these songs… everybody did. Long before I get involved with Billy (Connolly) and got involved with playing in the so-called folk scene I knew a lot of that stuff anyway. CI: Did you ever perform many traditional songs? GR: Not publicly because I started writing songs myself when I was 15 or 16 in the mid-‘60s due to these people like the Beatles and Bob Dylan and the whole songwriting thing. By the time I me Billy Connolly in 1969 I’d written quite a few songs of my own and I was much more interested in singing and performing them. CI: Was there a sense of elitism that traditional music at the time was considered very unhip? GR: Oh yes, that was part of it. There was a pub we used to drink in Glasgow called The Scotia. That was the pub where all the folkies met and at that time the regulars were people like John Martyn – though in those days he was called Ian McGeeey. One day a guy walked through the door and said "Is this the Scotia?" He had a fiddle and said he was from the Shetlands so we got him to play in a session and he was amazing. That was Aly Bain. And people like Rab Noakes and Barbara Dickson. She was a good example of someone who at the time was singing straight traditional folk music, and wonderfully so too. CI: Do you see any of those people now? GR: Oh yes, Billy and I have been talking about a little project. CI: Not a Humblebums reunion? GR: No, STV wanted to do a documentary on my career and they’ve asked various people to get involved and Billy’s one of them. It should be good fun. CI: Wasn’t there some bad blood with Billy Connolly at one time? GR: Yes. When Billy and I went our own separate ways it was quite amicable at the time because it was obvious that Billy’s jokes were getting longer and longer and the songs were getting shorter and shorter. It seemed the wise thing to do was split. The monologues were about twenty minutes long and we had my two-minute songs sandwiched between the jokes. So Billy was developing more and more as a comedian and I was developing more and more with my music, so I went off and formed Stealers Wheel. We both said a couple silly things after to the Melody Maker or something. Nothing to worry about. We’ve met subsequently and it’s fine. CI: Did you forsee that Billy would become a big star as a comedian? GR: Yes I did. I knew he was a real talent. I think at the time we split up I had more confidence that he would go on to do great things; then he did. I always knew he was that good. Billy and I had a really good couple of years. We were real good friends and I believed it showed when we worked together. Probably my best years on the road were spent with Billy. CI: Did you make much money at the time? GR: Not really. But I’d been on the dole before I met Billy and it was good from the point of view that we travelled light – just an acoustic guitar and a banjo – and for a concert I suppose we got about £100 which was cash in hand. And we weren’t married or anything, so it was good fun. CI: Are you planning to go back on the road now? GR: I’m toying with the idea. I may play a few dates at the Edinburgh Festival and if it feels good I may take it a stage further. But the performing thing has never been a great need in me. Some people are driven by it – if they don’t do a gig for a couple of days they’re climbing the walls, but I’m not like that. CI: So are you planning another album? GR: Yes, I’m thinking of doing something very low-key and sparse, just acoustic instruments and get away from the very produced sound. Just do something very direct – so I’m writing songs now with that in mind. |

||